For people who have experienced violence, the image of violence summons all the senses surrounding violence at once. That sensation is inevitable and does not depend on the perceived realism of the image. Even the image of violence in animation, for instance, becomes a channel that can always be directly connected to violence in memory. In that regard, the scene of an explosion is a familiar image to us despite being an unfamiliar event. An explosion at once removes what was there and destroys what was intact; it attacks the surface from above and below without warning and nullifies the traces accumulated on the surface. In short, an explosion is a pure kind of violence. However, scenes of explosions in news, documentaries, films, and photos do not stimulate much of a sense of shock, especially if seen several times a day. Perhaps we are desensitized to the image of the explosion. Instead of sympathizing with the image of a threat that we have never experienced and digesting pain in our own ways, we simply dissolve all images within an extension of the “selfie.” When it comes to the image of an explosion, we need to understand that we have long since lost the function of our sense of pain. The reason may be that the place where images of explosions are stored and consumed is no different from the place where other advertisements and selfies are uploaded. In that light, can a painting depicting an explosion change something?

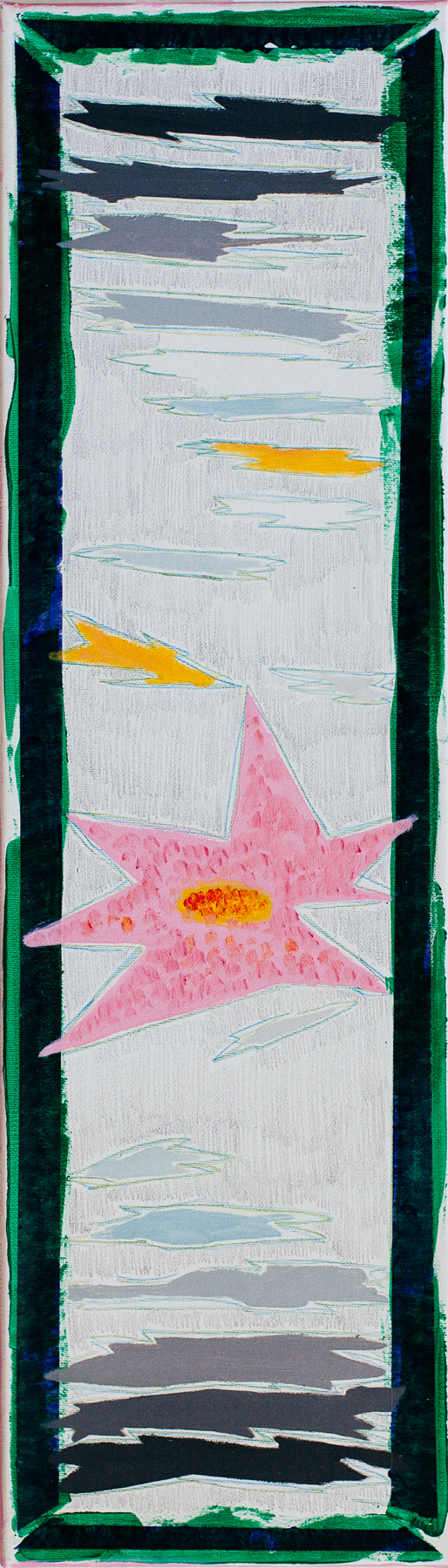

Yang-ha seems to have explored the “thin emotion” between the world and the self in many ways. That feeling, which can never be quelled, appeared at times as the face of a familiar, harmless teddy bear and, at other times, as the face of an angry Maria. The image of the explosion, which she has been dealing with since 2020, can also be read as an extension of the same “thin emotion.” Maria, as a tearful icon of resistance, and the curse of a flat, two-dimensional explosion share the absolute world of the Bible. By contrast, in Yang-ha’s work, the image of the explosion has gradually established itself as the symbol of an independent phase. Yang-ha once said, “I’m attracted to the image of the explosion.” Attraction is an emotion with a strong motivation of the kind that is always outside language and sometimes the clearest but truest emotion. In the process of guessing the artist’s attraction or imagining the sensory path of attraction, the kind of conflict that piqued the artist’s interest seems irrelevant. The image of the explosion that she has created within the canvas does not indicate the perpetrator or victim of the explosion being referred to—that is, the central figure. Instead, explosions stand on their own as self-sufficient images.

She mocks the masculine desire for violence and war and instead thrusts herself into the military industrial complex with stubborn irony and cynicism. The phallic missile is transformed into a flattened and voluminous portrait of an explosion. The safety of the home and garden have become archaeological sites of tragedy and disaster.

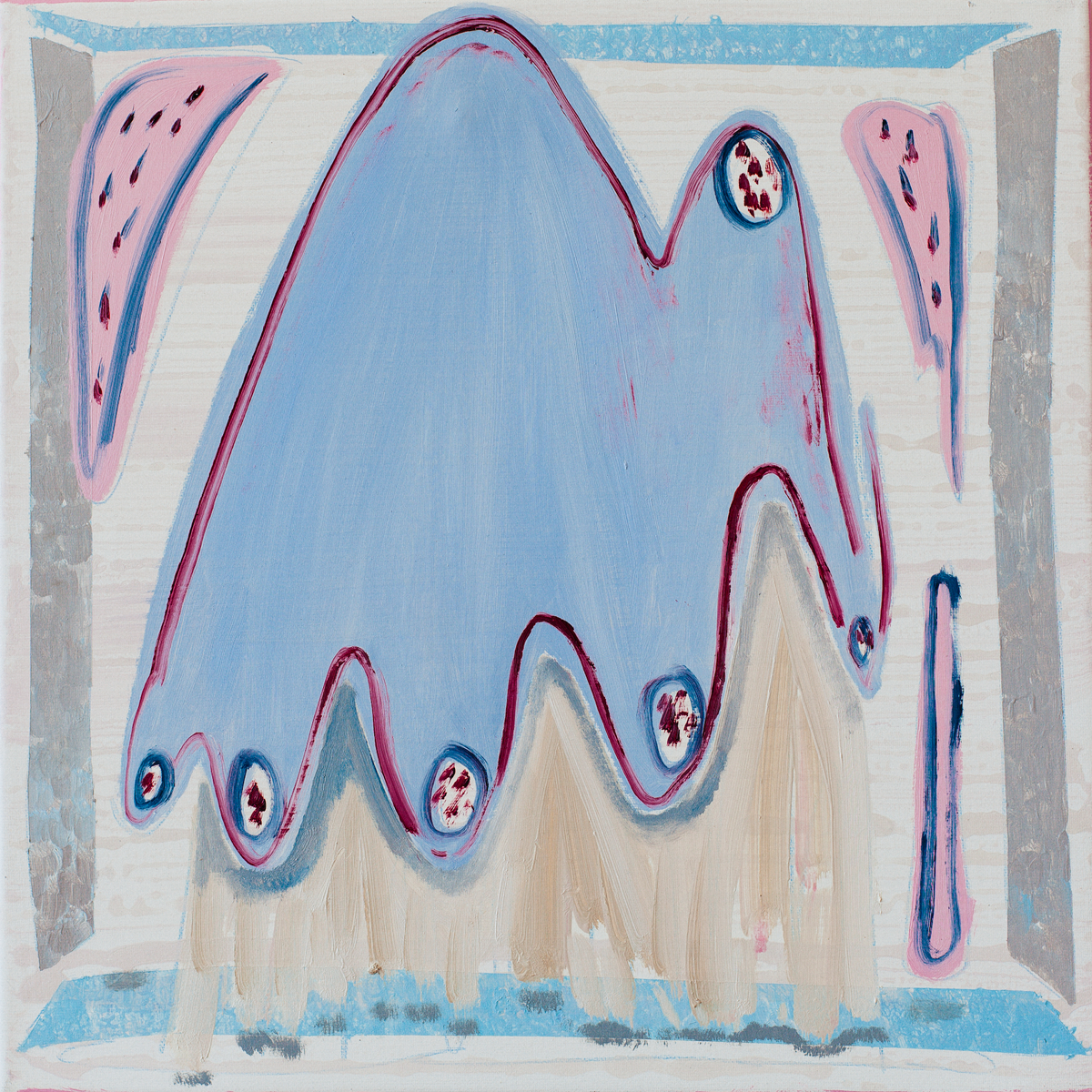

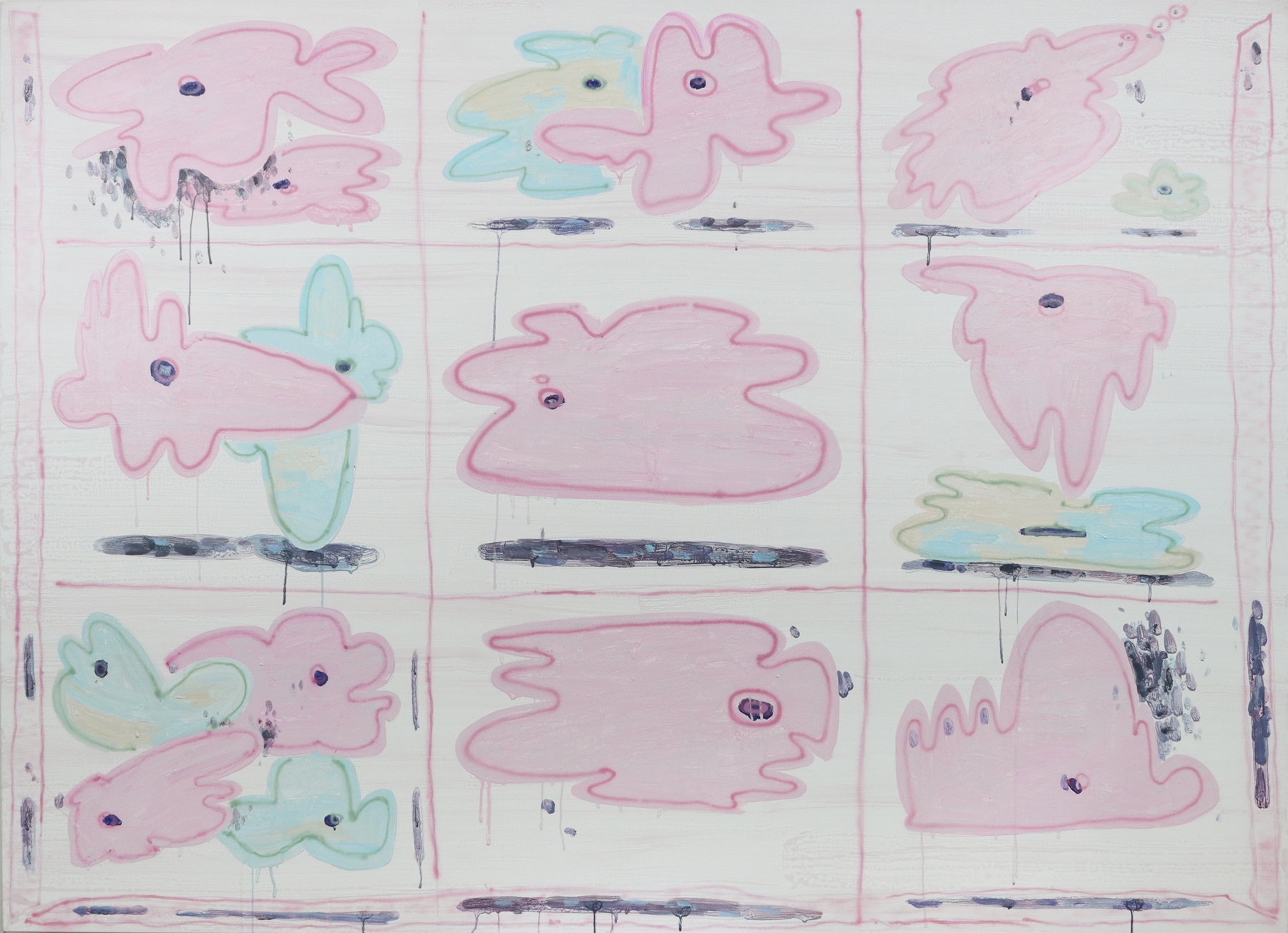

Even so, the image of the explosion created by Yang-ha is not to be read as depicting a natural phenomenon. It feels more similar to an artificial explosion caused by a bomb or missile, but that also remains unclear. However, the place with the remains of the explosion and the smoke rising from an unknown time only distract the mind away from any judgment that the explosion was caused by a natural phenomenon. The place is a space with its own rules. Each space has a different size, color, and transparency, and the arrangement of windows and balconies varies as well. Nevertheless, in Yang-ha’s work, the place always points to a single space. As a place with room to connect different semantic networks, it is also to be read above all as a performative area where the artist repeatedly trains and commits herself. That performativeness is similar to the attitude of forging the thin emotions between the self and the world such that they never become dull. Among her paintings, which seem to inattentively emphasize the presence of explosions, the ones with conspicuous edges on the side of the canvas accentuate the spatial experience. Yang-ha creates a space that can continue to speak within the canvas; however, the speech therein has no sound. Even the explosion, which overwhelms the human scale and is likely to have the loudest roar, has no sound in Yang-ha’s paintings. It lies in complete silence. The more clearly the explosion takes form in the silence, the more subtly the tension expands. Standing in front of Yang-ha’s paintings, everyone becomes a witness without any way to escape. As much as the outline of the spray paint or colored pencil added as the final process of painting feels hopeful and bright, the painting nevertheless grins coldly and cynically. Just as when the corner of a character’s mouth slowly rises in a tragic situation where laughter is impossible, the vigorous cheerfulness and laughter in the fresh, lightly colored painting share space with the emotion of revenge with an unclear target. In that respect, the explosions in Yang-ha’s paintings create an ambivalent semantic network. As seen in the title of her series, Well, It’s a Scene Made to Cry, So I Will, Yang-ha’s language is akin to a final joke about misery, or optimism about paralyzed sensory functions that seem impossible to recover.

In some of Yang-ha’s paintings, the image of the explosion gradually becomes vegetal, similar to a flower in full bloom. Others seem to suggest a still life in a peaceful indoor space. An explosion may appear within another explosion, or the image of the explosion may evolve into an image that seems to divide itself. As a result, the different reactions and semantic systems surrounding explosions that cannot be reduced to language also become factors that further abstract Yang-ha’s image of the explosion. In other words, in the explosion translated into the artist’s image-based language, figurative imagery with any direct, clear meaning is eliminated. Similar to inherited trauma, the potential of the sensation aroused by the image becomes clear only by way of the source for the individual who senses it. In that process, the unclear event of an explosion is converted into an individual experience that each viewer has experienced, and the image does not direct the real event but instead brings about a unique image for all viewers. That experience is no longer related to the firsthand experience of an explosion; instead, it is a solution of Yang-ha’s for dealing with the everlasting challenge of how artwork awakens an individual’s efficacy. Sculptures of explosive clouds that sometimes protrude from Yang-ha’s paintings may add clues. Such sculptures, in which the artist outlines a piece of wood ‘like drawing’ and piles up layers again ‘like drawing,’ don’t capture the sense of someone watching the explosion within the canvas. Explosions have always been, from the beginning, scattered outside the picture.

Altogether, Yang-ha’s statement actively reveals ironic characteristics; weak, easily scattered things are brought together densely and imbued with presence, while grave, serious things are treated simply and childishly. Yang-ha seems to discover her own tireless interest as her exploration of explosive images continues to occupy her for longer than she expected. If so, some questions are bound to follow. For one, how much can an explosion as a pure image, in which the layer of social meaning and historical context clinging to the event of the explosion is removed, be the root of rich creation? For another, does the variation of the explosion continuously create aimless pleasure? How might the space containing the explosion disappear if external light and atmosphere are introduced? In other words, when does the window, as a permanent fixture, open? Above all, when can the narrator and viewer watching the space where the explosion occurs go outside?

Purgatory Imploded, 2024

Purgatory Imploded, 2024 Open the Window 오픈더윈도우, 2023

Open the Window 오픈더윈도우, 2023 The Alert Rings at Noon on the First Monday of Every Month, 2022

The Alert Rings at Noon on the First Monday of Every Month, 2022 Perhaps, It Will Carry On, 2021

Perhaps, It Will Carry On, 2021 I Pretend to be Okay but, I'm not Okay, 2021

I Pretend to be Okay but, I'm not Okay, 2021 Voluntary Error

Voluntary Error Brrr 부르르, 2024

Brrr 부르르, 2024 REVERSE ENGINEERING

REVERSE ENGINEERING  Homely 홈리, 2023

Homely 홈리, 2023 It's a Blast, You're Welcome, 2022

It's a Blast, You're Welcome, 2022 Sleepless Remote 희미한 불면증, 2020

Sleepless Remote 희미한 불면증, 2020 Misson of Gravity 중력의 임무

Misson of Gravity 중력의 임무